Birds mostly are small and difficult to see well with only the unaided eye. A pair of binoculars is essential for birding. The good news is that this likely will be the only thing you have to buy, and the cost need not be high.

You might also want some knowledge about the birds you will observe and about how to observe them.

Buying Binoculars

We recommend using binoculars with eight, ten, or (maybe) twelve magnification and an objective lens diameter between 30 and 50 mm. Binoculars usually are specified by these two numbers, for example as being 8×40.

The larger the objective lens diameter, the more light in your view, and the larger your field of view. More magnification narrows your field of view but makes things look larger.

Our personal preference is 10×42, as the field of view is still large and more details are visible, particularly when birds are distant. Now that binoculars are made of lightweight materials and streamlined construction, the weight difference is negligible between these and smaller ones.

Binoculars with 12x magnification have grown in popularity and users seems pleased with them. For looking at still, perching birds they should be fine, but they will make it harder to stay focused on birds that move often, like warblers, or on birds in flight.

We also appreciate having close focus ability, that is, being able to focus on birds nearby, which some binoculars cannot do. How close? Our binoculars can still focus at eight feet, but if you can get twelve feet or better you probably will be pleased. Sometimes birds land nearby and give amazing views, and you don’t want to miss those.

We don’t recommend so-called “compact” binoculars for birding, though some birders carry these around in a handbag for unexpected bird encounters when doing other things.

Read more about choosing and understanding binoculars here.

Advances in manufacturing have made good binoculars affordably priced. This used to not be the case, and older online guides recommend spending much more than is necessary today.

We think that adequate binoculars can be had online for $50 or so, likely similar in quality to what we used in our first few years of birding. These Gosky 10×42 binoculars are $65 after you apply the coupon, for example.

If you spend more, you can get sharper views: better construction, better glass, better coatings.

These Vortex Diamondback HD binoculars ($229) are excellent in all regards and come with a lifetime warranty against any damage, even if the damage was your fault. They are similar in quality to what we use now.

Shop around. There are many manufacturers and choices. The mentions above are simply examples, and we do not receive any payment or consideration for them.

Birding Knowledge

Once you have binoculars, you are going to want to go birding. You will find that you can bird almost anywhere, that birds are around us even in the middle of urban areas like Manhattan, where we do our birding.

Of course, you will find a greater variety of birds in parks and on and along bodies of water.

How you go about birding is up to you. If you are more social, you might want to go with some friends, perhaps with some who already know a bit about birding.

We liked going to the park and experiencing nature on our own. It’s up to you.

We started by simply observing birds, looking and listening, and then trying to figure out what they were. This deductive process can be a lot of fun. We would remember the details of the bird, saving its image in our mind, and then check online and in a guide book to try to match what we observed to a species.

Now the process is even easier, and you can do it in the field thanks to the excellent and free Merlin Birding app.

Once you have downloaded this app to your smartphone, it will suggest birding packs of photos and sounds to further download. Download the pack relevant to where you live. For example, we use the US: Northeast pack.

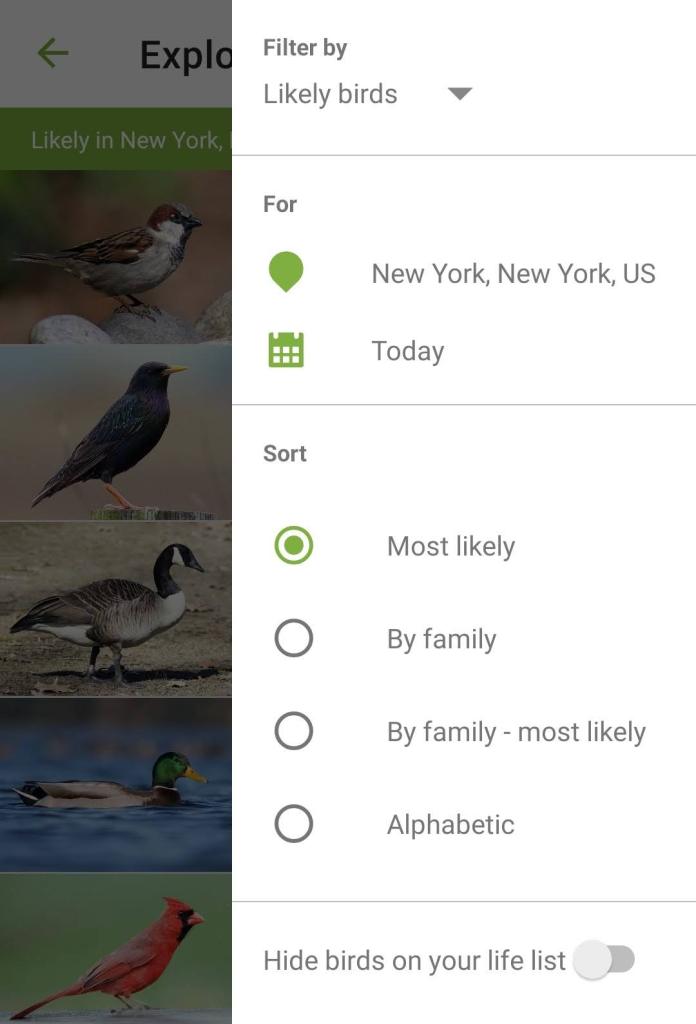

Now you can set up one of the most useful features of Merlin: you can have it display the birds you are likely to encounter in your area in approximate order of their abundance.

Go to the menu at the top, right-hand side and choose “likely birds.” Further select for current location (which the app will suggest), Today, and sort by “Most likely.”

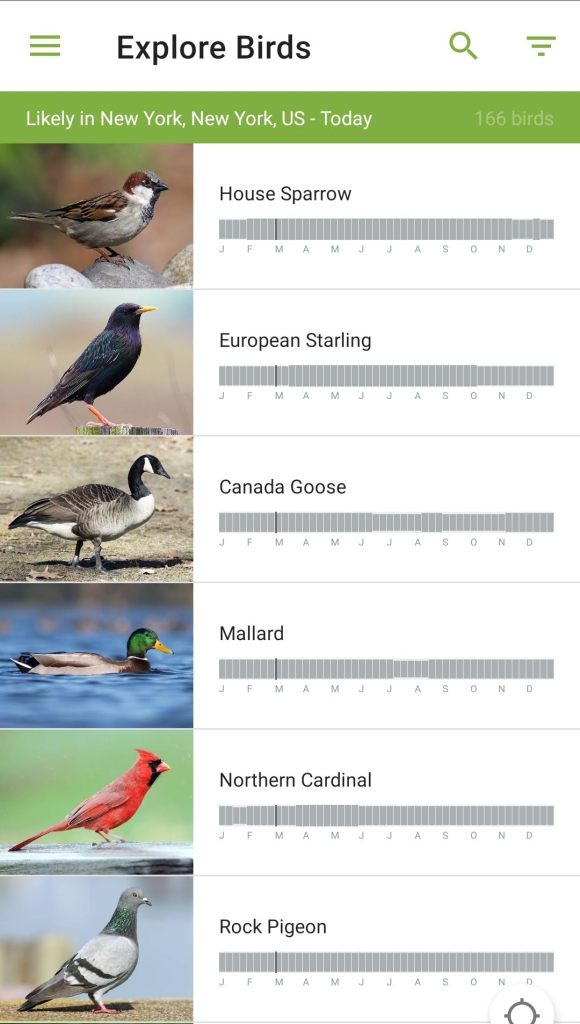

Now the app should display something like this:

The bar graph displayed shows relative abundance of the species in your area during different times of the year.

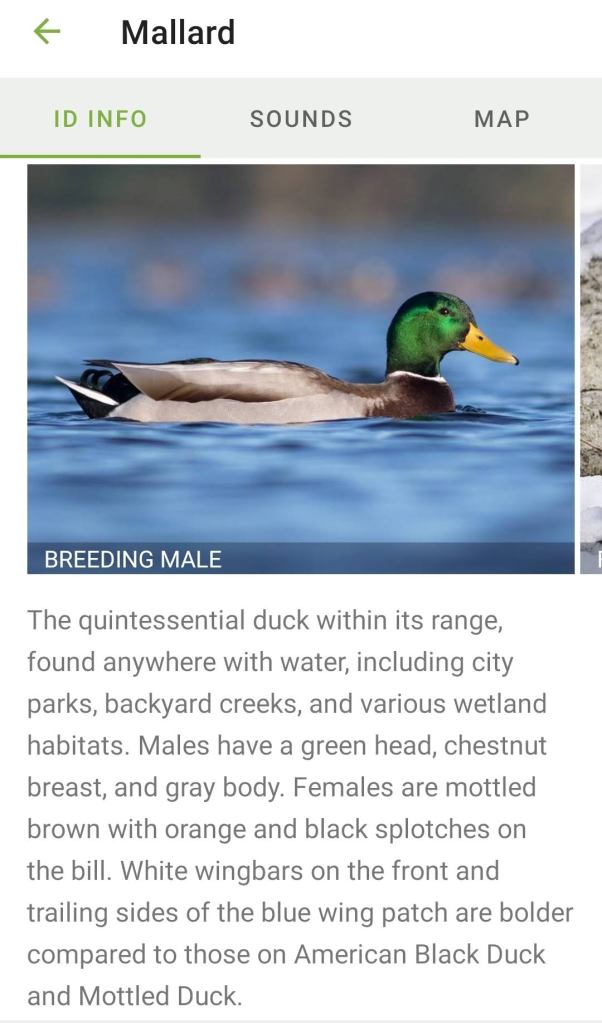

These are indeed the most common birds in our area. You can go right down the line and learn a bit more about them, including more photos (which are useful because often male and female birds look different and appearance may vary depending on the time of year).

For example, the Mallard:

We suggest quickly reviewing the fifteen to thirty most common birds in your area before you go birding. You can then enjoy the thrill of recognition, and you will have an idea of what to expect.

The most prevalent beginner-birder mistake is thinking that some common bird is actually some other rare bird. By using the “likely” sort in Merlin, and focusing first on learning the most common birds, you can do much to avoid this error.

The Merlin App also has a powerful bird-photo identification tool driven by AI. With good photos, we find that it is almost always right (90+%) in suggesting the most likely species. The app also can identify your birds by asking you questions.

When you want to learn more about a bird species—what habitats if prefers, what it eats, how and where it breeds, etc.—visit Cornell’s AllAboutBirds website, which has a wealth of information not only on each species but on birds in general.

In particular, we recommend the Bird ID Skills section of this site, which has excellent instruction on how to become better at birding.

Once you can reliably identify most of the birds you encounter, consider making a free account on eBird and using it to track what you observe and find out what others are reporting.

We run Manhattan Bird Alert on Twitter. Our daily posts of alerts, photos, videos, and commentary have helped many to learn birding or to enjoy it more. Check it out!

Now is a good time to begin your learning, starting with the common birds. By the end of May over 90 new bird species will have passed through Manhattan in addition to those already observed this year. The arrival pace stays fairly manageable through mid-April and then a torrent of birds arrives in early May.

Best to you on your birding!