1) Download the free Merlin Bird ID app from Google Play or the App Store.

2) The app will ask to further download packs of birding photos and sounds. For New York City birding, you will need the US: Northeast pack, so choose this one. If you want other packs, too, that’s fine.

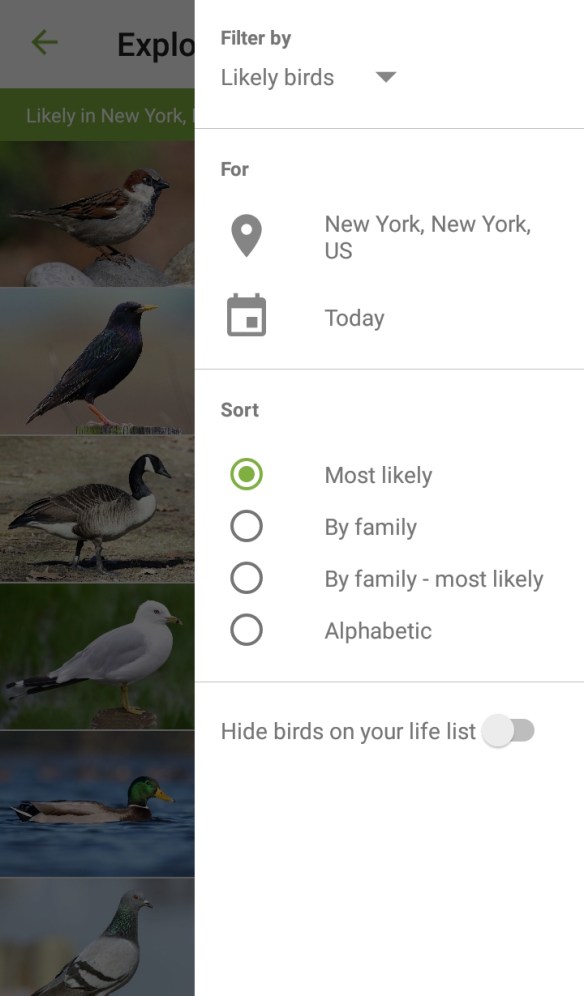

3) Go to the menu at the top, right-hand side and choose “likely birds.” Further select for current location (New York, NY presumably), Today, and sort by “Most likely.”

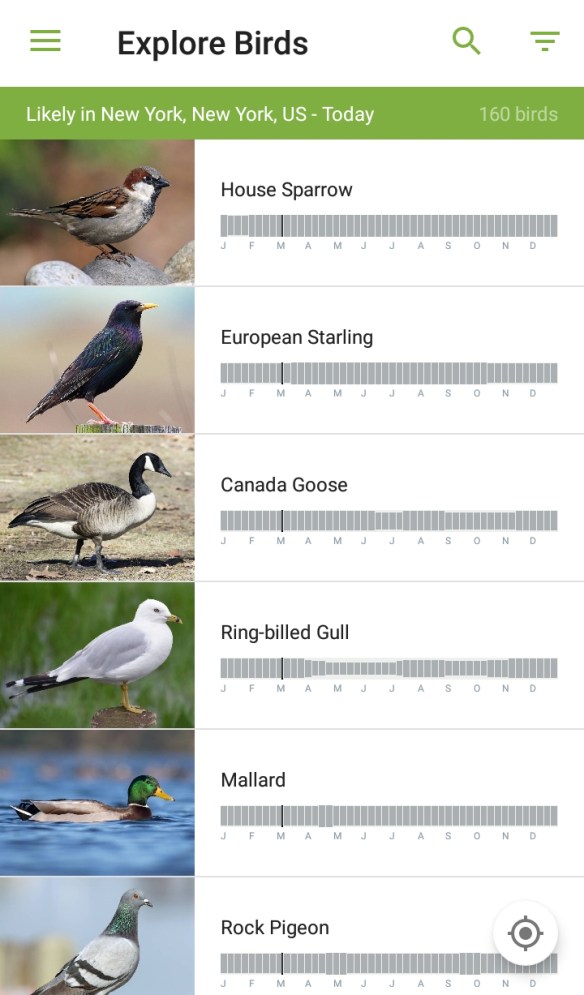

4) You’re done! The app should now be displaying something like this:

The app displays birds roughly in the order of how abundant they are now at the location you have selected, which for us is New York City. This ordering is useful, as you want to learn the most common birds first, as they are the ones you will see most often and you do not want to be confused about them.

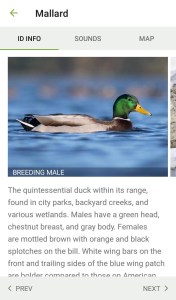

Clicking on any element of the list takes you to an entry containing more photos of the bird, a brief description of the bird’s behavior and appearance, recordings of its sounds, and a map of the species’ range:

Remember that males and females of any given species might look different, as is the case with Mallards, and also with Buffleheads, Hooded Mergansers, and many others. Likewise, many birds differ in plumage based on age, like Bald Eagles and Ring-billed Gulls. Furthermore, some species look different depending on whether it is breeding or nonbreeding season for them. Spring is breeding season for nearly every species, so for now you can focus on the photos that depict breeding plumage.

Identifying birds based on their songs and calls is a more advanced birding skill, but a most rewarding one. The Merlin app has the basic sounds you need to get started.

The first 30 to 40 birds on the Merlin list should be fairly common anywhere in New York City. After that, differing habitats come into play. Because they have large coastal and saltmarsh areas, Brooklyn and Queens commonly get waterfowl and shorebirds that are quite rare for Manhattan. Current examples, for early March, are Horned Grebe and Long-tailed Duck.

Nevertheless, Manhattan does exceptionally well at getting songbirds during spring migration, and birders come from all over the world to visit Central Park and observe these birds in April and May. At least one hundred new bird species for the year will pass through Manhattan between now and the end of May.

By starting now, you can be ready to recognize the colorful birds of spring as they arrive. Different species have different arrival patterns, but in general, each has a two-week period of highest likelihood, some longer, some shorter. Any individual bird might spend only a day or two in Central Park before moving on, though some, like Cedar Waxwing and Gray Catbird, will stay for the summer and breed in the park. You continue to see many of the same migrant species day after day (until the species as a whole has passed through), however, because as some individual birds depart, others arrive.

Spring migration begins slowly, so time prior to mid-April is good for learning. You might even want to skip ahead in the Merlin settings and look, not at today, but at some future date to see what will be arriving. By late April, the new arrivals can come at a furious pace, perhaps even ten new species on a single day. It’s an exciting and beautiful time! With the Merlin app, you can be ready for it.

For instruction on how you can best assimilate all this knowledge and use it in the field, see the four Inside Birding videos from the Cornell Lab’s Bird Academy.