I took this photo and release it with a Creative Commons BY-SA license.

Birds mostly are small and difficult to see well with only the unaided eye. A pair of binoculars is essential for birding. The good news is that this likely will be the only thing you have to buy, and the cost need not be high.

You might also want some knowledge about the birds you will observe and about how to observe them.

Buying Binoculars

We recommend using binoculars with eight, ten, or (maybe) twelve magnification and an objective lens diameter between 30 and 50 mm. Binoculars usually are specified by these two numbers, for example as being 8×40.

The larger the objective lens diameter, the more light in your view, and the larger your field of view. More magnification narrows your field of view but makes things look larger.

Our personal preference is 10×42, as the field of view is still large and more details are visible, particularly when birds are distant. Now that binoculars are made of lightweight materials and streamlined construction, the weight difference is negligible between these and smaller ones.

Binoculars with 12x magnification have grown in popularity and users seems pleased with them. For looking at still, perching birds they should be fine, but they will make it harder to stay focused on birds that move often, like warblers, or on birds in flight.

We also appreciate having close focus ability, that is, being able to focus on birds nearby, which some binoculars cannot do. How close? Our binoculars can still focus at eight feet, but if you can get twelve feet or better you probably will be pleased. Sometimes birds land nearby and give amazing views, and you don’t want to miss those.

We don’t recommend so-called “compact” binoculars for birding, though some birders carry these around in a handbag for unexpected bird encounters when doing other things.

Read more about choosing and understanding binoculars here.

Advances in manufacturing have made good binoculars affordably priced. This used to not be the case, and older online guides recommend spending much more than is necessary today.

We think that adequate binoculars can be had online for $50 or so, likely similar in quality to what we used in our first few years of birding. These Gosky 10×42 binoculars are $65 after you apply the coupon, for example.

If you spend more, you can get sharper views: better construction, better glass, better coatings.

These Vortex Diamondback HD binoculars ($229) are excellent in all regards and come with a lifetime warranty against any damage, even if the damage was your fault. They are similar in quality to what we use now.

Shop around. There are many manufacturers and choices. The mentions above are simply examples, and we do not receive any payment or consideration for them.

Birding Knowledge

Once you have binoculars, you are going to want to go birding. You will find that you can bird almost anywhere, that birds are around us even in the middle of urban areas like Manhattan, where we do our birding.

Of course, you will find a greater variety of birds in parks and on and along bodies of water.

How you go about birding is up to you. If you are more social, you might want to go with some friends, perhaps with some who already know a bit about birding.

We liked going to the park and experiencing nature on our own. It’s up to you.

We started by simply observing birds, looking and listening, and then trying to figure out what they were. This deductive process can be a lot of fun. We would remember the details of the bird, saving its image in our mind, and then check online and in a guide book to try to match what we observed to a species.

Now the process is even easier, and you can do it in the field thanks to the excellent and free Merlin Birding app.

Once you have downloaded this app to your smartphone, it will suggest birding packs of photos and sounds to further download. Download the pack relevant to where you live. For example, we use the US: Northeast pack.

Now you can set up one of the most useful features of Merlin: you can have it display the birds you are likely to encounter in your area in approximate order of their abundance.

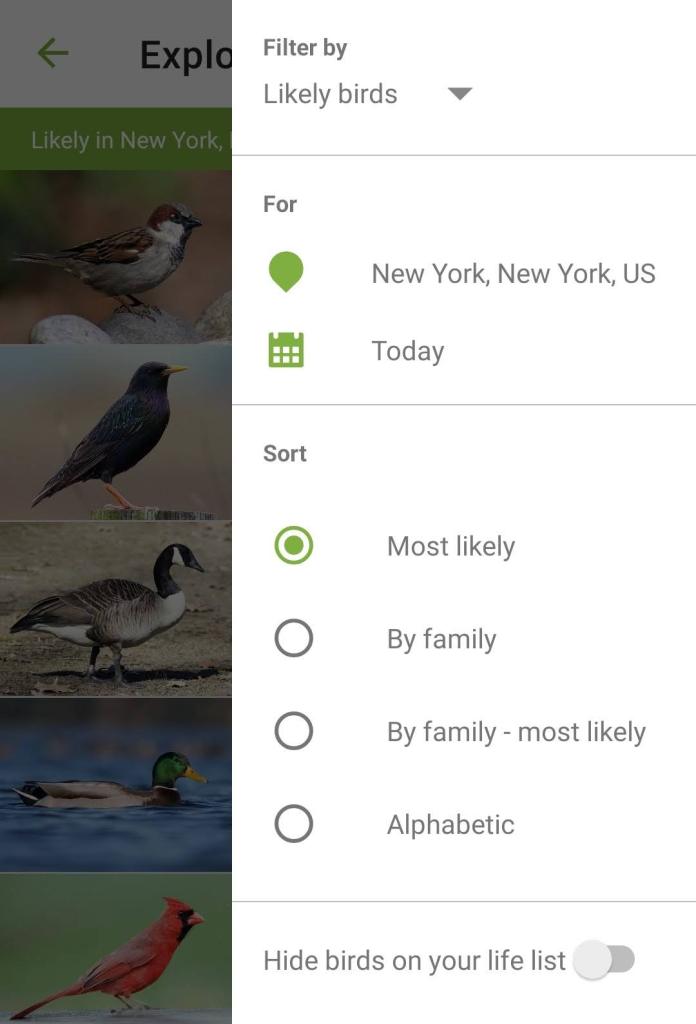

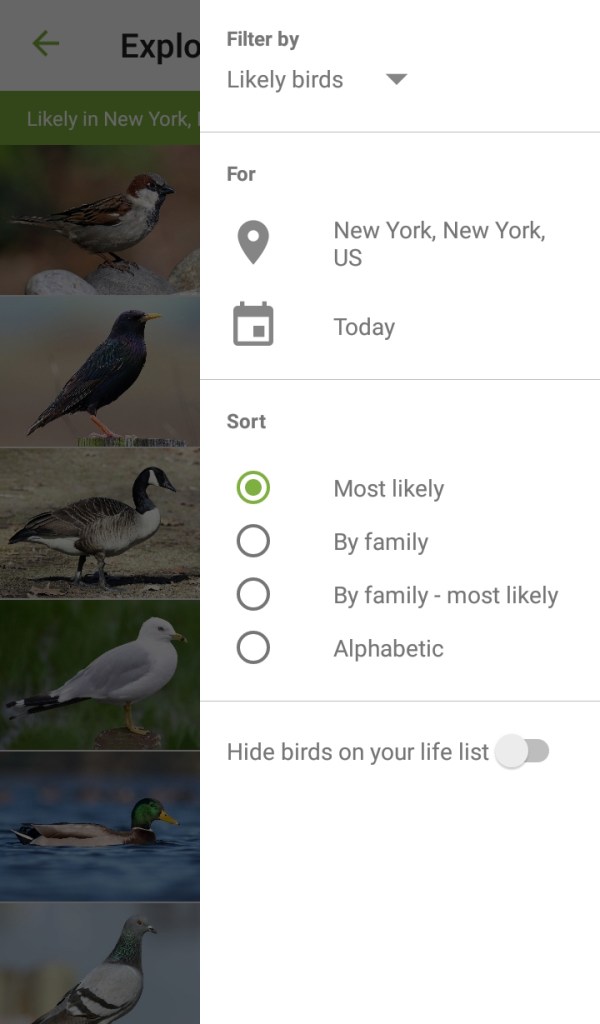

Go to the menu at the top, right-hand side and choose “likely birds.” Further select for current location (which the app will suggest), Today, and sort by “Most likely.”

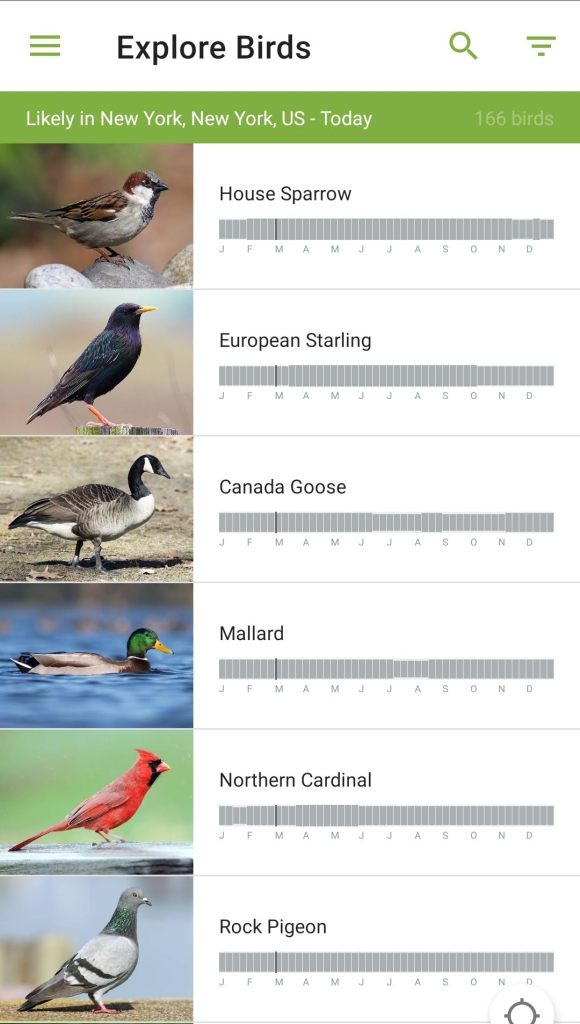

Now the app should display something like this:

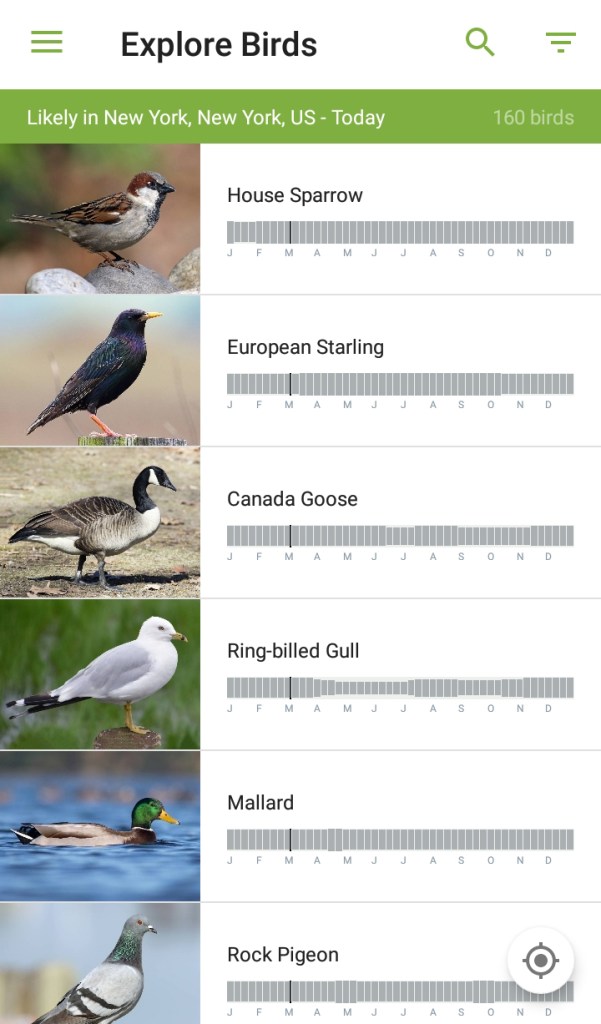

The bar graph displayed shows relative abundance of the species in your area during different times of the year.

These are indeed the most common birds in our area. You can go right down the line and learn a bit more about them, including more photos (which are useful because often male and female birds look different and appearance may vary depending on the time of year).

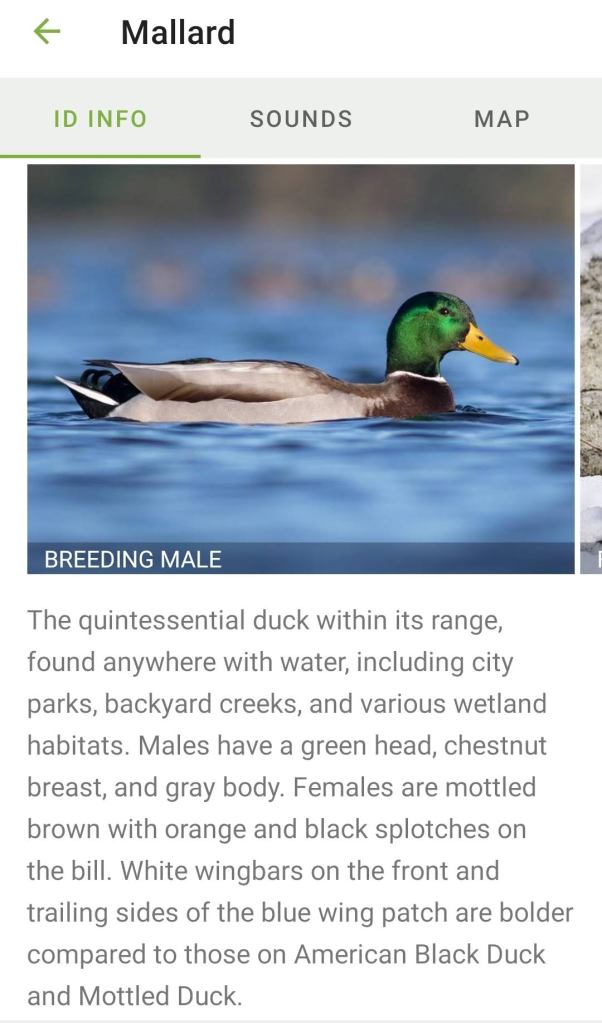

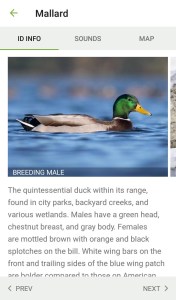

For example, the Mallard:

We suggest quickly reviewing the fifteen to thirty most common birds in your area before you go birding. You can then enjoy the thrill of recognition, and you will have an idea of what to expect.

The most prevalent beginner-birder mistake is thinking that some common bird is actually some other rare bird. By using the “likely” sort in Merlin, and focusing first on learning the most common birds, you can do much to avoid this error.

The Merlin App also has a powerful bird-photo identification tool driven by AI. With good photos, we find that it is almost always right (90+%) in suggesting the most likely species. The app also can identify your birds by asking you questions.

When you want to learn more about a bird species—what habitats if prefers, what it eats, how and where it breeds, etc.—visit Cornell’s AllAboutBirds website, which has a wealth of information not only on each species but on birds in general.

In particular, we recommend the Bird ID Skills section of this site, which has excellent instruction on how to become better at birding.

Once you can reliably identify most of the birds you encounter, consider making a free account on eBird and using it to track what you observe and find out what others are reporting.

We run Manhattan Bird Alert on Twitter. Our daily posts of alerts, photos, videos, and commentary have helped many to learn birding or to enjoy it more. Check it out!

Now is a good time to begin your learning, starting with the common birds. By the end of May over 90 new bird species will have passed through Manhattan in addition to those already observed this year. The arrival pace stays fairly manageable through mid-April and then a torrent of birds arrives in early May.

Best to you on your birding!

I hope that everyone is following @BirdCentralPark on Twitter, because that is where the action is: daily bird reports, photos, and videos. With 19,000 followers now, @BirdCentralPark has become one of the largest birding-focused accounts on Twitter. I put a lot of time into providing high-quality content on it and on our other borough-based accounts: @BirdBronx, @BirdBrklyn, and @BirdQueens.

This website still attracts a healthy amount of daily traffic, though, so for the sake of completeness, I want to mention two new life birds from 2019.

The first, White-winged Dove, occurred months prior, on April 14. An experienced birder reported this mega-rare vagrant after 3 pm at Evodia Field in the Central Park Ramble. It stayed there the rest of the afternoon, feeding on the ground with many Mourning Doves beneath the bird feeders. Though this was an excellent habitat for White-winged Dove, the bird was not observed there, or anywhere else in the area, in the following days—a one-day wonder.

White-rumped Sandpiper, Inwood Hill Park, August 10, 2019

The other life bird showed up mere days ago, first on August 9. The rising tide quickly submerges the Spuyten Duyvil mud flats at Inwood Hill Park, so that by the time I received an eBird notice of a White-rumped Sandpiper there, it was too late to reach the flats in time to see it. I tried later in the afternoon anyway, as sandpipers have been congregating on the rocks, but had only a flyover Lesser Yellowlegs.

With moderate migration taking place the night of the 9th, I held little hope that I would re-find the White-rumped Sandpiper there the next day at noon low tide. As I was on my way to Inwood Hill from Sherman Creek, though, another birder did exactly that. I ran over to her and quickly confirmed her find, and issued the alert on Twitter.

I had been waiting a long time to get that bird, nearly five years. One had been found on 4 October 2014 near the same location, at the adjacent Muscota Marsh. The finder did everything he could to help me get it, even personally calling me. But I was in downtown Manhattan, and I did not pick up the alert in time. Even if I had picked it up right away, I would have had to leave dinner quickly to arrive before the bird went out of view.

1) Download the free Merlin Bird ID app from Google Play or the App Store.

2) The app will ask to further download packs of birding photos and sounds. For New York City birding, you will need the US: Northeast pack, so choose this one. If you want other packs, too, that’s fine.

3) Go to the menu at the top, right-hand side and choose “likely birds.” Further select for current location (New York, NY presumably), Today, and sort by “Most likely.”

4) You’re done! The app should now be displaying something like this:

The app displays birds roughly in the order of how abundant they are now at the location you have selected, which for us is New York City. This ordering is useful, as you want to learn the most common birds first, as they are the ones you will see most often and you do not want to be confused about them.

Clicking on any element of the list takes you to an entry containing more photos of the bird, a brief description of the bird’s behavior and appearance, recordings of its sounds, and a map of the species’ range:

Remember that males and females of any given species might look different, as is the case with Mallards, and also with Buffleheads, Hooded Mergansers, and many others. Likewise, many birds differ in plumage based on age, like Bald Eagles and Ring-billed Gulls. Furthermore, some species look different depending on whether it is breeding or nonbreeding season for them. Spring is breeding season for nearly every species, so for now you can focus on the photos that depict breeding plumage.

Identifying birds based on their songs and calls is a more advanced birding skill, but a most rewarding one. The Merlin app has the basic sounds you need to get started.

The first 30 to 40 birds on the Merlin list should be fairly common anywhere in New York City. After that, differing habitats come into play. Because they have large coastal and saltmarsh areas, Brooklyn and Queens commonly get waterfowl and shorebirds that are quite rare for Manhattan. Current examples, for early March, are Horned Grebe and Long-tailed Duck.

Nevertheless, Manhattan does exceptionally well at getting songbirds during spring migration, and birders come from all over the world to visit Central Park and observe these birds in April and May. At least one hundred new bird species for the year will pass through Manhattan between now and the end of May.

By starting now, you can be ready to recognize the colorful birds of spring as they arrive. Different species have different arrival patterns, but in general, each has a two-week period of highest likelihood, some longer, some shorter. Any individual bird might spend only a day or two in Central Park before moving on, though some, like Cedar Waxwing and Gray Catbird, will stay for the summer and breed in the park. You continue to see many of the same migrant species day after day (until the species as a whole has passed through), however, because as some individual birds depart, others arrive.

Spring migration begins slowly, so time prior to mid-April is good for learning. You might even want to skip ahead in the Merlin settings and look, not at today, but at some future date to see what will be arriving. By late April, the new arrivals can come at a furious pace, perhaps even ten new species on a single day. It’s an exciting and beautiful time! With the Merlin app, you can be ready for it.

For instruction on how you can best assimilate all this knowledge and use it in the field, see the four Inside Birding videos from the Cornell Lab’s Bird Academy.

Mandarin Duck by Gus Keri

Last week a certain duck became a media sensation, and I was taken along for the ride. Gus Keri’s video of the male Mandarin Duck at the Central Park Pond, posted on my Manhattan Bird Alert Twitter account, had already gone viral over two weeks prior, when the duck first appeared there on October 10.

Jen Carlson of Gothamist interviewed me and wrote the story that introduced the broader New York world to the mysterious Mandarin Duck. Then the duck frustrated everyone by disappearing two weeks. I thought he had been eaten by a raptor.

But on October 25 we learned that the Mandarin Duck lived on, seen at the 79th Street Boat Basin on the Hudson. By Sunday, October 28, the Mandarin Duck had returned to the Central Park Pond.

Julia Jacobs of the New York Times met with me to view the duck on October 30, and her brilliant story was published early the next morning. It quickly became the most popular story on the New York Times website and was liked tens of thousands of times on Twitter.

Since then, I have been doing a great many interviews with reporters from news organizations all over the world about the Mandarin Duck, which continued to draw hundreds of admirers to the Central Park Pond this last weekend hoping to see and, better yet, take a photo or video of the vibrantly-colored bird.

Many are finding joy in observing the Mandarin Duck, and I am delighted that my alerts account has been able to help them locate him and display their footage.

Let’s be clear: this Mandarin Duck is of domestic origin. He is not a wild bird, and he certainly is not ABA-countable or eligible for the eBird database.

Right now, though, he is New York City’s most famous duck, and we are glad to have him.

Sandhill Cranes have a southern breeding range not too far north of Manhattan, in upstate New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. They frequently stopover in nearby Somerset, New Jersey, during migration. They breed in wetlands, and they will touch down in those or in expansive grasslands. They are not likely ever to land in Manhattan, and they are known to fly very high when migrating, which explains why they are so rarely observed here despite having a nearby presence and being large, unmistakable birds.

It never occurred to me that they even were a possibility until a birder reported one flying over the Bronx Zoo in May 2016. A report of seven Sandhill Cranes flying over Fort Tryon Park in Manhattan followed in December 2016. Then three more were seen over Fort Tryon in January 2017 by the same observer. It’s likely that another two were seen from midtown over the Hudson in December 2017.

These observations stoked my interest, but I saw no practical way to get the birds. Sandhill Crane appearances were not part of a daily movement pattern — they were notably infrequent. Plenty of birders were reporting from the Inwood area most days and not seeing any cranes. A dedicated Sandhill Crane watch of any length would almost certainly produce none. Still, it was a species to keep in mind.

Yesterday, 16 October, I went to Inwood Hill Park to do some sky-watching and river-watching. It was a decent, sunny morning with moderate northwest winds, and I was seeing some Bald Eagles floating overhead. Brant flocks were moving low down the Hudson.

At 11:48 a.m. I saw high-flying bird over Inwood Hill with just my eye and I focused my binoculars on it. It clearly was not a goose or a raptor. It had long, broad wings beating slower than a goose’s would, a long, outstretched neck, and feet trailing outstretched behind it. As it turned into sunlight, I noticed grey wings and body, and briefly a pale cheek patch and darker crown — a Sandhill Crane, flying southwest over the Hudson.

With only three other birders on record as having observed a Sandhill Crane in Manhattan in three other occurrences, the species must be considered among the rarest few I have had here. The North American population appears to be continuing a multi-decade trend of population increase, so perhaps it will appear here more frequently in the future.

Dickcissel, Central Park North End

On migration-season Fridays, Robert DeCandido offers a birding walk in the Central Park North End. He starts early, 7 a.m. or so, well before the scheduled walk time of 9 a.m., to scout the area and also to get in some good birding at the best time.

Two weeks ago he found Orange-crowned Warbler and Yellow-breasted Chat on his scouting walk, the first of which he tweeted while I was still in bed, so the chase took a bit longer than I would have liked.

On this last Friday, August 24, I was up earlier, so that when Robert’s 8:00 a.m. tweet of a Dickcissel opposite the Green Bench arrived, I did not have much left to do to before going on my way.

It’s remarkable how this small area, around the Green Bench, produced two rarities worthy of regional mention in a short time frame.

I ran and reached the location by 8:27, and within a minute I saw the Dickcissel poking its head above the grass. I even got a decent photo.

Dickcissel is not recorded every year in the park; the last known appearance of it there was noted by only one birder in October 2016. Before that, Robert DeCandido and Deborah Allen found one on the Central Park Great Hill on 27 May 2016, and I quickly chased it and saw it along with Deborah.

I am delighted to have had at least one Dickcissel in Manhattan every year from 2011 to 2018.

Today, August 25, Robert DeCandido continued to produce. I joined him for a walk around the Ramble on a pleasant but not-too-birdy morning. The Ramble was alive with the calls of Red-breasted Nuthatches. Altogether I had at least ten of them.

We saw and heard several of them in the trees of Bunting Meadow, immediately north of the Upper Lobe. Robert noticed another, drabber bird associating with the nuthatches, one with brown streaking on the breast and a sharp bill — an unexpected Pine Siskin, the first of the year for Manhattan! This also is the earliest-recorded fall date on eBird of a Manhattan Pine Siskin.

After warning Manhattan birders from my @BirdCentralPark Twitter feed that Thursday-night radar was lighting up and that the morning could bring some good birds, I planned on looking for shorebirds in Inwood. I had already observed nearly every bird likely to occur in Central Park in the spring.

Those plans changed quickly, on Friday, 10 August 2018, when Robert DeCandido sent a 7:56 a.m. alert of Orange-crowned Warbler in the Central Park Wildflower Meadow, a species I still needed for the year. (As did nearly everyone else. Unlike 2017, when Orange-crowned Warbler was seen often during spring migration, 2018 brought perhaps only one such bird, seen on only one day.)

As I was getting ready to run to the North End, DeCandido found and reported another rarity: Yellow-breasted Chat southwest of the A. H. Green Bench, near the Wildflower Meadow.

The temperature was rising quickly (it would reach 86 F later) and it was a sunny day, so I knew that bird activity would soon decline. I ran to the Wildflower Meadow and looked around.

I did not see or hear any migrants, so I went to check the Green Bench area, which also had no birds of interest.

I knew that the species I was seeking almost surely were still in the area, whose dense foliage offered excellent habitat. I also knew that DeCandido and his birding group would be coming by soon, so I continued looking.

Half an hour later DeCandido and group arrived. Having Robert DeCandido around is a tremendous advantage, because DeCandido is a master of using sound to attract birds.

I have birded with him extensively, and I can relate dozens of times when no migrant activity was evident, yet after DeCandido played appropriate calls for a minute or two, warblers, vireos, and flycatchers would appear in nearby trees.

Such was the case again. We began seeing expected migrants like Canada Warbler, American Redstart, and Yellow Warbler. We even had an early Black-throated Blue Warbler.

Then DeCandido spotted the Yellow-breasted Chat again, in a fruiting tree on the northwest side of Wildflower Meadow, and everyone had great views of the perching bird.

Then we moved to the southwest corner of Wildflower Meadow, and the sounds DeCandido played drew in warblers to trees that had been empty before our arrival. We had Red-eyed Vireo, another Canada Warbler, an empidonax flycatcher, and a couple American Goldfinches.

After much waiting we noticed some rustling low in the brush, and DeCandido soon had everyone on a handsome Orange-crowned Warbler.

DeCandido’s observations of Yellow-breasted Chat and Orange-crowned Warbler set the earliest-ever records for fall migration for these species, the latter by over a month. A most remarkable morning in Central Park!

Bicknell’s Thrush (from allaboutbirds.org)

This morning Roger Pasquier heard the song of a Bicknell’s Thrush at Evodia (the Ramble bird feeder area). He later told Anthony Collerton about it and pointed out the bird, a warm-toned thrush associating closely with a grayer Gray-cheeked Thrush. Collerton issued a Manhattan Bird Alert (follow @BirdCentralPark on Twitter) to let everyone know. He himself had not heard the bird sing.

I arrived at Evodia some minutes later, after Collerton had left, and quickly found a pair of thrushes on the east side of Evodia that matched the stated description. I announced my find to other birders nearby just as the bird was flying to the west side of Evodia.

As I have written before, visual identification is not sufficient to claim a Bicknell’s Thrush, as Gray-cheeked can look much the same. One needs to hear the Bicknell’s song, which ends with a thin, rising pitch.

Both thrushes were staying silent and had wandered out of view. When we started playing the Bicknell’s song on a mobile phone, one of the thrushes came back into view and perched overhead, calling “whee-er”. Soon it flew down and sang. We had our Bicknell’s!

Shortly thereafter I called it in again for Anders Peltomaa and Al “Big Year” Levantin and elicited singing in response. Same later for Joseph DiCostanzo and his American Museum of Natural History walk.

I also heard the Bicknell’s Thrush sing on its own, unprompted, just east of the Gill Source at 10:18 a.m.

A half-hour later Robert DeCandido came by Evodia and helped members of his birding walk see and hear a singing Bicknell’s Thrush.

American Bird Conservancy President Mike Parr and his group were nearby at the time and might have heard the Bicknell’s song. To be sure, I used my phone to call it back again and everyone got close views of the calling and singing bird.

Bicknell’s Thrush remains a rarity not just in Central Park but throughout its tight migration range along the East Coast. Since identification requires hearing its song, it is possible to get it only during spring migration. Even then, the time window seems to be narrow — I have never had Bicknell’s on more than one day in any May, and there are usually at most only a few days in any May when I hear much thrush song in Central Park. The possible date range for it here seems to be May 12 to May 25, judging by historical Central Park records and my own experience.

When I saw Kevin Topping’s 5:05 p.m. tweet of a “possible” Kirtland’s Warbler on the northwest side of the Central Park Reservoir, I immediately relayed it to Manhattan Bird Alert (@BirdCentralPark). Of course I had some doubts — Kirtland’s Warbler had only one confirmed eBird record in all New York State (2014, Hamlin Beach State Park on the shore of Lake Ontario), and a female Canada Warbler would be at least 10,000 times more likely.

By 5:15 I had heard from a friend that Kevin was “fairly sure,” so I got ready to chase. Along the way I received a photo of the bird, which strongly supported the ID.

Because I did not know the exact location of the bird, I ended up taking the longer route around the east side of the Reservoir. I finally saw Kevin at 5:31 p.m. at 91st Street and West Park Drive, but he no longer was on the bird.

Then Ryan Zucker arrived, and soon he and his mother had re-found the bird slightly northwest of the previous location. From that point forward the bird stayed in view, sometimes moving from tree to tree but remaining in the same general area, where it had an abundance of insects on which to feed. It had been a hatchout day in the park, and many other warblers were enjoying the feast.

On the way I had privately posted Andrew Farnsworth of the find, and by 5:58 p.m. he had it, too — the only bird native to the continental United States that he had not yet recorded.

It likely is the rarest bird that has been found in Manhattan during the time I have been birding. By the time I left at 6:29 p.m. over 100 birders were on the scene.

Surely some birders will be traveling to Central Park tomorrow from all over the region, hoping to re-find this bird. Manhattan Bird Alert will try to keep everyone informed!